The Dreaded Day

To my great consternation (since I had already convinced myself that I was a

very sick person) the Medical Board that examined me for fitness to do

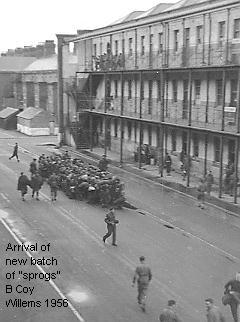

National Service thought otherwise and declared me to be in rude health. So in July 1956 I duly

reported to Waterloo Station and boarded a train with hundreds of other deeply unhappy young men

and travelled miserably to the less-than-exotic location of Aldershot, Hampshire, for basic training.

"Bring back National Service" has always been a popular cry in Britain, and I am always surprised that

some of the people repeating this mantra actually did National Service themselves! I suppose there

were some plus points: some people learned skills they might otherwise not have obtained. For myself,

I have never regretted being turned into a touch-typist (would you believe!). Also, I am sure that being

uprooted from the home environment eased the passage from boyhood to independent manhood. But

the downside was that all these young men who, whilst being deemed too young even to enjoy the

right to vote for their Government, were nevertheless deemed old enough to be sent into war

situations in remote parts of the world and be killed.

I suppose that if National Service were to be reintroduced now for eighteen year-olds then at least this time

they would be old enough to vote!

Putting Square Pegs in Round Holes

Basic training brought out the best and the worst in us. Those who lacked confidence became the

victims of those who didn’t. Those who were known to have had experience in school cadet forces

were given responsibility for marching their platoons from A to B when the NCOs couldn’t be bothered

to do it themselves. I was one such, and so found myself (without the benefit of any visible rank)

yelling at my fellow squaddies, and showing off my own drill skills to those poor unfortunates who had

not previously worn a uniform. As a means of gaining respect and popularity this was about as effective

as spitting in someone’s face.

During the first couple of weeks’ basic training (at Blenheim Barracks) each of us was interviewed by

an officer to establish in what direction we should be encouraged to go. Would we be put forward for a

Commission? (Even National Servicemen were picked (usually on a "class" basis) as potential 2nd

Lieutenants.) Would we become lorry drivers? Would we become cooks? Would we become

infantrymen, wireless operators, mechanics? If we were not potential officers, could we be potential

Non-commissioned Officers (NCOs)?

The officer who interviewed me appeared to make an early decision (from my accent?) that I was not

officer material. Having decided that I ought at least to try and enjoy myself, I said I would like to

drive a lorry: after all, the RASC was responsible for, amongst other things, transport. In line with what

passed for military logic this resulted in my being ear-marked as an Army Clerk! I was sent to the RASC

2 Training Battalion, Willems Barracks, to be suitably trained. The Royal Army Service Corps (variously

referred to as "Run Away Someone’s Coming" the "Royal Army Shit Corp" and the "Royal Army Skirt

Chasers") not only provided the army with its transport but also its clerical services, i.e., short-hand

writers, typists, secretaries, filing clerks, and so on.

Military Type

The Army had, in its wisdom, decided that I should join a "Clerical

Battalion".

The Pen is mightier than the Sword?

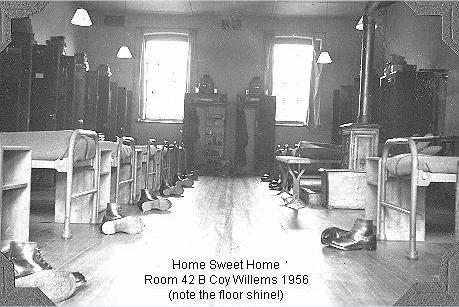

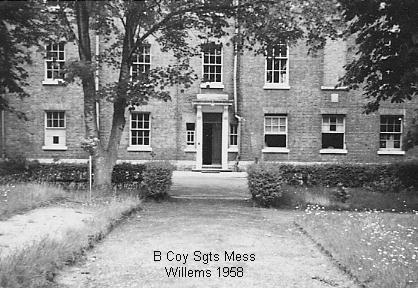

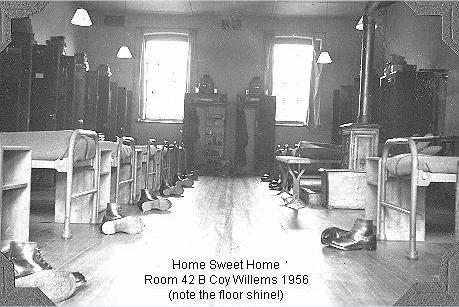

So I - with my fellow sufferers earmarked as clerks - headed for 2

Trg Bn at Willems Barracks where the next four weeks were spent

completing basic training in drill and weaponry, combined with

training in basic typing skills and the mysteries of memos, files and

dockets.

For the typing we were assembled in a class room equipped with

rows of ancient typewriters. The sergeant in charge taught us the

position of the "home keys".

You hover the left hand over A S D and F, and the right hand over : L K and J. From here all other keys can

be reached merely by moving one’s fingers forwards or backwards, and/or slightly to right or left. The next

thing is to remember where all these keys are without looking at the keyboard; this skill came fairly quickly

to most of us, (1) because we did nothing else for two hours at a time, and (2) because when a man wearing

three stripes tells you to do something you don’t argue.

Within a few days the Sergeant was playing marching music on a record player at the front of the class,

and we were copy-typing pieces of text in strict time to the beat, without taking our eyes off the

paper.

Fifty years later I am sitting in front of a computer keyboard typing this account at sixty words per minute

without looking at the keys, grateful to the Army for this particular ability.

From Typist to “Drill Pig”

For all my quickly-developing skills as an army typist, I nurtured no desire

to serve out the rest of my National Service sitting in Army offices, be

they brick or canvas. Whilst many of my comrades were keen to be sent

abroad, my unadventurous disposition was more inclined to keeping out of

war zones, and preferably staying within commuting distance of home. It

was at this time that Prime Minister Anthony Eden’s Suez Crisis

developed. I was very keen to avoid any opportunity to go and kick the

Egyptian President’s backside in that particular bungled operation.

I soon learned there was a continual need for National Service NCOs to

help train up further intakes of miserable young men, appearing as they

did every four weeks on the National Service conveyor belt. Again, calling

on my experience as a Sergeant in the school cadet force, I was able to

gain rapid promotion to Lance Corporal on completion of my basic training, and it wasn’t too long

before I was a full Corporal and feeling pretty damned pleased with myself.

This added a few shillings to my miserable weekly pay, so there was added cash to spend on packets of

five "Park Drive" or "Woodbines", or - more nutritiously - double portions of baked beans in the NAAFI.

Armed with my new stripes and a long stick with a silver knob on the end

I was assigned to help a National Service Sergeant in marching squads of

men up and down the drill square, right-turning, left-turning and about

turning, shouldering arms, ordering arms, standing to attention, standing

at ease and standing easy. Other duties included ensuring that a barrack

room full of men got up in the morning in time to wash, shave, dress,

clean the room, lay out kit in regulation order, have breakfast and be on

parade by 07.30 hours.

How I admired our National Service Sergeant Copage! Immaculately

turned out with his toe caps reflecting the early morning sun, he had a

voice that could be heard two miles away, and a fine selection of

personal insults to heap on the first poor soul to swing his right arm

forward at the same time as his right leg went forward. (There was

always one!) I resolved to model myself on Sgt Copage. In a rare burst of

ambition, I thought that if he could make sergeant before reaching the

age of twenty, then so could I.

This ambition to reach sergeant before completion of National Service was the first of only a very few

instances in my life when I set a specific target for my future.

You may think that you can control your life, map out your future, set your long-term targets. I advise

caution. If you must have an ambition, stick to generalities and don’t be too specific. Life has a nasty habit

of moving (or removing) your targets before you’ve had time to hit them. The more you plan in detail, the

more you lay yourself open to disappointment.

Look at where you would like to go and set your compass, but don’t draw a detailed route map. You don’t

have to be religious to appreciate one of the greatest pieces of advice from Jesus: "Give no thought for the

morrow, for sufficient unto the day are the evils thereof." In today’s English, if you spend all your time

worrying about the future, there’s no happiness; there are enough of today’s problems for you to be

worrying about.

It has been said that there is no destination in life - the journey is everything. I don’t know who said it. I

think I just did.

The late, great Willie Rushton, interviewed shortly before his untimely death in 1997 about his own

National Service experiences said,

"…the NCOs we always viewed as traitors because they were all NATIONAL SERVICE men and

almost invariably DEEPLY UNPLEASANT."

With the benefit of hindsight plus increasing maturity I have to acknowledge that Rushton's comment

could have applied to me. It is not a period of which I am particularly proud. I sometimes recall,

though, to make myself feel better, that not one my men ever tried to throw a brick at the back of my

head on a dark night, and some intakes even clubbed together and bought me a gift at the end of their

training. This was very gratifying, though not, I think, well deserved.

But I worked with National Service colleagues who were more fanatical than me. One Corporal (who

used to keep his brilliantly shiny "best" boots in a cardboard box wrapped in tissue paper, and was thus

known to all as "Boots") was such a perfectionist that on one occasion when we were working together

on the parade ground he insisted on putting his squad through their miserable paces right through the

sacred "NAAFI Break" because they were not measuring up to his exacting standards. This tall, thin

gangly youth of nineteen, with his razor-sharp creases and his glittering boots, yelled and bawled

obscenities at his victims, and their consequent efficiency was in inverse proportion to the volume of

the shouting. They were not going to get any better because they were tired, and all they could think

about was the fact that they were being denied the opportunity of getting their mug of tea and

lighting up a Woodbine. Whatever else I might have been I did believe in fair play, and things were

getting so objectionable that I gave a direct order to this maniac to dismiss his men. It was several

weeks before he could bring himself to speak to me again, and I didn’t regard this as a great loss.

During those days if you were in a Training Battalion, the majority of the personnel were conscripted

National Servicemen, and these included the NCOs and junior commissioned officers, but naturally

there was a core of regular soldiers at the heart of the system: the lieutenants, captains, majors, and

colonels on the commissioned side, and on the non-commissioned side, the sergeants, staff sergeants,

company sergeant majors and regimental sergeant majors. National Service NCOs rarely had time in

two years to make it beyond sergeant, nor National Service officers beyond 2nd lieutenant.

Some of us had a nasty habit of referring to the professionals as "Thick Regulars", for we could not

imagine that anyone with an ounce of intelligence would actually have chosen this way of life as a

career! The antipathy operated in both directions. In the Sergeants’ Mess, the National Service

sergeants were looked down upon by the regulars as presumptuous upstarts. No doubt similar feelings

existed in the Officers’ Mess, but possibly restrained under a more gentlemanly veneer; perhaps not.

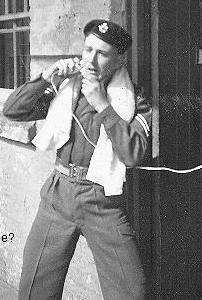

The truth of the matter was, if we were honest, that although it was easy to

identify some regular soldiers (and National Servicemen!) who were a couple of

rounds short of a full magazine, many were intelligent and honourable men. I

was glad to regard some of them of as my friends. Our B Coy Sergeant Major-

and here he is on the right - was a really first-class character with a sense of

humour and a genuine regard for the men under his command. I had forgotten

his name but I am grateful to George Goult (ex-NS sergeant who was discharged

a month before me) who wrote to me in 2008 and put me out of my misery. This

was CSM SYMES - a gentleman.

On the other hand, the Company Commander was one of the vilest characters

I’ve had the misfortune to meet: sarcastic, supercilious, vindictive and arrogant,

with a distinctly cruel streak, and the owner of a large Mercedes-Benz which

sparkled and gleamed down to the number plate screw heads, thanks to the

detailed attention required of any soldier who was given the unfortunate task of

cleaning it to his satisfaction. I also forgot this man's name, but I am grateful (I

think!) to Peter Claridge (who entered Willems for trade training in November 1957) for e-mailing me

with the missing name .. Major McCarten-Mooney.

Racism in the Army, Navy and Air Force has been a topical subject during recent years. There have

been some widely reported cases of anti-black feeling in certain regiments, (especially the Guards)

involving bullying and harassment, leading to the victims’ resignation from the Service.

All the more heartening to recount, therefore, that during my two years in Aldershot back in the

deeply prejudiced mid-1950s, I did not encounter active racism in my particular part of the RASC. In

fact I recall very clearly one recruit of Afro-Caribbean origin who I came to know quite well; he was

keen on pursuing a similar path to me through National Service, i.e., stay in Aldershot as a Drill

Instructor. I was already a sergeant by this time, and was in a position to recommend him for

promotion to Lance Corporal. He attained this without any opposition, and within a year, he became a

Corporal. He eventually made sergeant. At no time were any eyebrows raised, snide remarks made, or

obstacles put in this man’s way.

Military Gastronomy

"An army marches on its stomach" it has been said. Well, the Willems cook-house was a miserable

place. The breakfast fried eggs, laid out in orderly ranks on the hot-plate in their hundreds, were a

constant gastronomical challenge. We could have played tennis with them. Other meals were either

tasteless or excessively greasy. At most eating sessions an officer (usually a National Service 2nd

Lieutenant) would do the rounds asking if there were any complaints. "No Sir, thank you, Sir" was the

usual reply, even if the food was appalling, which invariably it was.

Again Willie Rushton’s experience is worth recounting:

"Everything all right, food all right?" - the Sergeant Major looking at us … I realised that I had found this leaf

- we were having some sort of stew, I don’t know what dead animal it was, but something obviously the Army

had bought en bloc. "Sergeant Major, there is a leaf in my stew." The Officer said, "That’s definitely a leaf."

So we paraded off, bringing the stew, to the kitchens, where there was a Sergeant Major, Cook, Head Chef

or whatever he was, standing there. "What’s this?" "It is a leaf. We can’t have leaves in the stew." The man

then pulled out this huge military manual of army cooking and turned to page 308 where it said: "Stew -

Other Ranks for the use of" and there was the "500 tons of beef, 4,000 tons of potato and onions - and - 1

bay leaf."

To give the Royal Army Catering Corps their due credit, if ever a special occasion came, such as a children’s

party or some other celebration, they could turn out a brilliant spread. Some of the most impressive

decorative iced cakes could have been seen in army kitchens.

After each meal we would troop out to a steaming metal bath of hot water in which we had to cleanse

our utensils (without the benefit of washing up liquid).

On occasions when we were out on major field exercises we would be introduced to the products of

army field kitchens. These included such culinary delights as tinned egg and bacon.

The grease that was not consumed with the food in the barracks cook-house eventually found its way

into the kitchen drainage system. At the rear of every cook-house was an enormous grease trap

designed to protect the town sewerage system from the ravages of military gastronomy, but which in

reality doubled up as a ready source of punishment for soldiers who fell foul of some disciplinary code

or other.

The worst punishment was to be told to don your "fatigues", open up the enormous lids to the stinking

black hole behind the cook-house, climb into it, then with a large scoop ladle out into buckets the

accumulated foetid layers of stinking greasy scum. This task always sorted out the men from the boys.

It was advisable always to follow up this activity with a long, hot bath!

Alcohol in Aldershot

There were at least ninety pubs in the town of Aldershot, and so we had ample opportunity during free

time to carry out experiments on how much alcohol could be poured into a young vertical human body

before it became a young horizontal human body. It was on one such expedition that I made first

contact with something called "rough" cider. The joke was that if you held your glass up to the light you

could still see pips and bits of apple core floating around, but the truth was that the term "rough"

related to (1) a high level of alcohol, and (2) how you would be feeling in a few hours time.

On that memorable summer evening, I and my thirsty comrades were having a cider drinking session in

one of Aldershot’s pubs. I was having a wonderful time, exchanging the best jokes in the world

(probably the worst jokes when sober), and had consumed about three pints of this fearsome brew in

very quick succession. I was laughing and joking with the best of them, but then I began to feel

somewhat detached from the world and decided to go outside into the street for some air.

It was then that I had the most remarkable experience: whilst I was standing bolt upright, the pavement

turned upwards through ninety degrees and hit me in the face!

It seemed an age before I deduced that both the pavement and I were horizontal. I staggered to my

feet and decided to try to walk back to the barracks. Although I accomplished this in due time, it was

through an eternity of nausea, and I am ashamed to say that Aldershot Corporation’s street cleansing

services would have been kept fairly busy the next day along my trail from the pub to the barracks.

When I got back to the barracks I had one last attempt at turning myself inside out in the nearest

ablutions block, then crawled up the stairs to my landing, where I vaguely remember being met by

some room mates, undressed by them, and put to bed. This was a little humiliating because I was at

that time the Room Corporal! Nobody mentioned it the next day and life went on as normal.

I have since come to the conclusion that allowing young people to make themselves thoroughly ill in a sea of

alcohol is probably not a bad thing, because the experience is so ghastly that it is unlikely to be repeated

(except by those with no intelligence). Certainly in my own case, whilst I plead guilty to becoming seriously

squiffy on special occasions, I have never ever repeated the rough cider experience.

Military Management Style

If you go on a typical management course you are taught how to motivate people, maintain their

respect and co-operation and achieve objectives by team work and good communication.

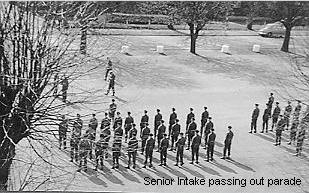

I learned during National Service that none of these aspirations was relevant to military operations. I

experienced an example of the peculiar military management style a few weeks after I had been

promoted to Sergeant. I was now a "Drill Pig", and so far as I was aware was successfully putting new

intakes through their drill training, passing drill competitions, and making a satisfactory spectacle for

proud parents who attended the Passing Out Parade at the end of basic training.

One Sunday night (actually it was 1 o’clock Monday morning) I returned to the Sergeants’ Mess having

used a week-end pass to go back home in Kingston trying to chat up girls. As usual, I was depressed.

Here I was, back amongst the gloomy buildings of Willems Barracks, with another week of square

bashing to look forward to. Just before I got to my room, I was intercepted by a Sergeants’ Mess

steward who had clearly been awaiting my return. I was tired, miserable, and ready for some sleep.

Then the bombshell: "You’d better come to the bar; you are in charge of it, as of now!"

So, while I had been away during the week-end, the Battalion Commander had decided, in the

interests of flexibility and general self-development that I should, without prior notice, be relieved of

my drill training duties and given responsibility for supervising the Sergeants’ Mess catering staff,

managing stock control in the Mess Bar, as well as actually serving behind the bar - which most nights

went on for indefinite periods, that is

until the last self-opinionated sergeant-

major couldn’t get any more beer down

his throat and felt like turning in for at

least two hours sleep before the next

Company Parade.

A more miserable time I have never had.

I had to manage sullen National

Servicemen who were deemed to be

good for nothing except to clean

kitchens and serve meals. Unlike my

green squaddies on the parade ground,

most of these guys didn’t give a damn

about my three stripes, and were as like

as not to beat me up if I tried too much

discipline. Their level of co-operation was in direct proportion to the amount of time they had left to

serve, which for most of them was very little.

At breakfast I was responsible for seeing that everyone got their eggs and bacon, and endless supplies

of toast, in good time for them to get out for their various duties. There was a big problem here, since

many of the people I was serving were senior in rank - staff sergeants, sergeant majors and so on,

some of whom were prone to rolling into the dining room rather late. I had received a direct order

from the Regimental Sergeant Major to stop serving breakfast at a particular time because of this

problem. When I tried to implement the Order, one of the staff sergeants who had come in late, sat at

a table which had been cleared because the deadline had passed, and demanded (indeed ordered) that

I should provide him with breakfast. No amount of reasoning would change his attitude, and when I

later complained to the RSM about it, he made it clear that it was my problem. On reflection, I

suppose it was: I should have refused the staff sergeant on the grounds that orders from the RSM took

precedence. But at the time I was not sufficiently mature.

It was a blessed relief after some weeks to be told that I was to resume normal training duties, these

being returned to me in the same perfunctory way as I had originally been relieved of them.

As a prisoner marks off the days on his cell wall, so we

marked off the days of National Service remaining to us.

As my count approached the two-year mark, I was

button-holed by the company sergeant major with an

invitation to sign on as a "Regular". He promised that

promotion to Staff Sergeant would be a certainty

immediately on signing up for another three years. As

usual, my vanity nearly got the better of me, but I was

relieved to hear myself say "No thank you, Sir."

(Remember "Boots"? ... he's behind me in the photo on

the right!)

A free Man of “Above-average Intelligence”

I left the Army with a surprisingly good reference from

the Commanding Officer written in the back of my

Certificate of National Service: Military Conduct: Very

Good. A non commissioned officer of above average

intelligence, ability and commitment; of excellent

character, he is absolutely loyal and trustworthy. He

has been an asset to his Battalion, as he must be to

any employer.

1st June 1958.

So I suppose I had a couple of things to be grateful for … the ability to touch-type, and a document

indicating that any employer would be mad not to put me on his payroll!

The Dreaded Day

To my great consternation (since I had already convinced myself that I was a

very sick person) the Medical Board that examined me for fitness to do

National Service thought otherwise and declared me to be in rude health. So in July 1956 I duly

reported to Waterloo Station and boarded a train with hundreds of other deeply unhappy young men

and travelled miserably to the less-than-exotic location of Aldershot, Hampshire, for basic training.

"Bring back National Service" has always been a popular cry in Britain, and I am always surprised that

some of the people repeating this mantra actually did National Service themselves! I suppose there

were some plus points: some people learned skills they might otherwise not have obtained. For myself,

I have never regretted being turned into a touch-typist (would you believe!). Also, I am sure that being

uprooted from the home environment eased the passage from boyhood to independent manhood. But

the downside was that all these young men who, whilst being deemed too young even to enjoy the

right to vote for their Government, were nevertheless deemed old enough to be sent into war

situations in remote parts of the world and be killed.

I suppose that if National Service were to be reintroduced now for eighteen year-olds then at least this time

they would be old enough to vote!

Putting Square Pegs in Round Holes

Basic training brought out the best and the worst in us. Those who lacked confidence became the

victims of those who didn’t. Those who were known to have had experience in school cadet forces

were given responsibility for marching their platoons from A to B when the NCOs couldn’t be bothered

to do it themselves. I was one such, and so found myself (without the benefit of any visible rank)

yelling at my fellow squaddies, and showing off my own drill skills to those poor unfortunates who had

not previously worn a uniform. As a means of gaining respect and popularity this was about as effective

as spitting in someone’s face.

During the first couple of weeks’ basic training (at Blenheim Barracks) each of us was interviewed by

an officer to establish in what direction we should be encouraged to go. Would we be put forward for a

Commission? (Even National Servicemen were picked (usually on a "class" basis) as potential 2nd

Lieutenants.) Would we become lorry drivers? Would we become cooks? Would we become

infantrymen, wireless operators, mechanics? If we were not potential officers, could we be potential

Non-commissioned Officers (NCOs)?

The officer who interviewed me appeared to make an early decision (from my accent?) that I was not

officer material. Having decided that I ought at least to try and enjoy myself, I said I would like to

drive a lorry: after all, the RASC was responsible for, amongst other things, transport. In line with what

passed for military logic this resulted in my being ear-marked as an Army Clerk! I was sent to the RASC

2 Training Battalion, Willems Barracks, to be suitably trained. The Royal Army Service Corps (variously

referred to as "Run Away Someone’s Coming" the "Royal Army Shit Corp" and the "Royal Army Skirt

Chasers") not only provided the army with its transport but also its clerical services, i.e., short-hand

writers, typists, secretaries, filing clerks, and so on.

Military Type

The Army had, in its wisdom, decided that I should join a "Clerical

Battalion".

The Pen is mightier than the Sword?

So I - with my fellow sufferers earmarked as clerks - headed for 2

Trg Bn at Willems Barracks where the next four weeks were spent

completing basic training in drill and weaponry, combined with

training in basic typing skills and the mysteries of memos, files and

dockets.

For the typing we were assembled in a class room equipped with

rows of ancient typewriters. The sergeant in charge taught us the

position of the "home keys".

You hover the left hand over A S D and F, and the right hand over : L K and J. From here all other keys can

be reached merely by moving one’s fingers forwards or backwards, and/or slightly to right or left. The next

thing is to remember where all these keys are without looking at the keyboard; this skill came fairly quickly

to most of us, (1) because we did nothing else for two hours at a time, and (2) because when a man wearing

three stripes tells you to do something you don’t argue.

Within a few days the Sergeant was playing marching music on a record player at the front of the class,

and we were copy-typing pieces of text in strict time to the beat, without taking our eyes off the

paper.

Fifty years later I am sitting in front of a computer keyboard typing this account at sixty words per minute

without looking at the keys, grateful to the Army for this particular ability.

From Typist to “Drill Pig”

For all my quickly-developing skills as an army typist, I nurtured no desire

to serve out the rest of my National Service sitting in Army offices, be

they brick or canvas. Whilst many of my comrades were keen to be sent

abroad, my unadventurous disposition was more inclined to keeping out of

war zones, and preferably staying within commuting distance of home. It

was at this time that Prime Minister Anthony Eden’s Suez Crisis

developed. I was very keen to avoid any opportunity to go and kick the

Egyptian President’s backside in that particular bungled operation.

I soon learned there was a continual need for National Service NCOs to

help train up further intakes of miserable young men, appearing as they

did every four weeks on the National Service conveyor belt. Again, calling

on my experience as a Sergeant in the school cadet force, I was able to

gain rapid promotion to Lance Corporal on completion of my basic training, and it wasn’t too long

before I was a full Corporal and feeling pretty damned pleased with myself.

This added a few shillings to my miserable weekly pay, so there was added cash to spend on packets of

five "Park Drive" or "Woodbines", or - more nutritiously - double portions of baked beans in the NAAFI.

Armed with my new stripes and a long stick with a silver knob on the end

I was assigned to help a National Service Sergeant in marching squads of

men up and down the drill square, right-turning, left-turning and about

turning, shouldering arms, ordering arms, standing to attention, standing

at ease and standing easy. Other duties included ensuring that a barrack

room full of men got up in the morning in time to wash, shave, dress,

clean the room, lay out kit in regulation order, have breakfast and be on

parade by 07.30 hours.

How I admired our National Service Sergeant Copage! Immaculately

turned out with his toe caps reflecting the early morning sun, he had a

voice that could be heard two miles away, and a fine selection of

personal insults to heap on the first poor soul to swing his right arm

forward at the same time as his right leg went forward. (There was

always one!) I resolved to model myself on Sgt Copage. In a rare burst of

ambition, I thought that if he could make sergeant before reaching the

age of twenty, then so could I.

This ambition to reach sergeant before completion of National Service was the first of only a very few

instances in my life when I set a specific target for my future.

You may think that you can control your life, map out your future, set your long-term targets. I advise

caution. If you must have an ambition, stick to generalities and don’t be too specific. Life has a nasty habit

of moving (or removing) your targets before you’ve had time to hit them. The more you plan in detail, the

more you lay yourself open to disappointment.

Look at where you would like to go and set your compass, but don’t draw a detailed route map. You don’t

have to be religious to appreciate one of the greatest pieces of advice from Jesus: "Give no thought for the

morrow, for sufficient unto the day are the evils thereof." In today’s English, if you spend all your time

worrying about the future, there’s no happiness; there are enough of today’s problems for you to be

worrying about.

It has been said that there is no destination in life - the journey is everything. I don’t know who said it. I

think I just did.

The late, great Willie Rushton, interviewed shortly before his untimely death in 1997 about his own

National Service experiences said,

"…the NCOs we always viewed as traitors because they were all NATIONAL SERVICE men and

almost invariably DEEPLY UNPLEASANT."

With the benefit of hindsight plus increasing maturity I have to acknowledge that Rushton's comment

could have applied to me. It is not a period of which I am particularly proud. I sometimes recall,

though, to make myself feel better, that not one my men ever tried to throw a brick at the back of my

head on a dark night, and some intakes even clubbed together and bought me a gift at the end of their

training. This was very gratifying, though not, I think, well deserved.

But I worked with National Service colleagues who were more fanatical than me. One Corporal (who

used to keep his brilliantly shiny "best" boots in a cardboard box wrapped in tissue paper, and was thus

known to all as "Boots") was such a perfectionist that on one occasion when we were working together

on the parade ground he insisted on putting his squad through their miserable paces right through the

sacred "NAAFI Break" because they were not measuring up to his exacting standards. This tall, thin

gangly youth of nineteen, with his razor-sharp creases and his glittering boots, yelled and bawled

obscenities at his victims, and their consequent efficiency was in inverse proportion to the volume of

the shouting. They were not going to get any better because they were tired, and all they could think

about was the fact that they were being denied the opportunity of getting their mug of tea and

lighting up a Woodbine. Whatever else I might have been I did believe in fair play, and things were

getting so objectionable that I gave a direct order to this maniac to dismiss his men. It was several

weeks before he could bring himself to speak to me again, and I didn’t regard this as a great loss.

During those days if you were in a Training Battalion, the majority of the personnel were conscripted

National Servicemen, and these included the NCOs and junior commissioned officers, but naturally

there was a core of regular soldiers at the heart of the system: the lieutenants, captains, majors, and

colonels on the commissioned side, and on the non-commissioned side, the sergeants, staff sergeants,

company sergeant majors and regimental sergeant majors. National Service NCOs rarely had time in

two years to make it beyond sergeant, nor National Service officers beyond 2nd lieutenant.

Some of us had a nasty habit of referring to the professionals as "Thick Regulars", for we could not

imagine that anyone with an ounce of intelligence would actually have chosen this way of life as a

career! The antipathy operated in both directions. In the Sergeants’ Mess, the National Service

sergeants were looked down upon by the regulars as presumptuous upstarts. No doubt similar feelings

existed in the Officers’ Mess, but possibly restrained under a more gentlemanly veneer; perhaps not.

The truth of the matter was, if we were honest, that although it was easy to

identify some regular soldiers (and National Servicemen!) who were a couple of

rounds short of a full magazine, many were intelligent and honourable men. I

was glad to regard some of them of as my friends. Our B Coy Sergeant Major-

and here he is on the right - was a really first-class character with a sense of

humour and a genuine regard for the men under his command. I had forgotten

his name but I am grateful to George Goult (ex-NS sergeant who was discharged

a month before me) who wrote to me in 2008 and put me out of my misery. This

was CSM SYMES - a gentleman.

On the other hand, the Company Commander was one of the vilest characters

I’ve had the misfortune to meet: sarcastic, supercilious, vindictive and arrogant,

with a distinctly cruel streak, and the owner of a large Mercedes-Benz which

sparkled and gleamed down to the number plate screw heads, thanks to the

detailed attention required of any soldier who was given the unfortunate task of

cleaning it to his satisfaction. I also forgot this man's name, but I am grateful (I

think!) to Peter Claridge (who entered Willems for trade training in November 1957) for e-mailing me

with the missing name .. Major McCarten-Mooney.

Racism in the Army, Navy and Air Force has been a topical subject during recent years. There have

been some widely reported cases of anti-black feeling in certain regiments, (especially the Guards)

involving bullying and harassment, leading to the victims’ resignation from the Service.

All the more heartening to recount, therefore, that during my two years in Aldershot back in the

deeply prejudiced mid-1950s, I did not encounter active racism in my particular part of the RASC. In

fact I recall very clearly one recruit of Afro-Caribbean origin who I came to know quite well; he was

keen on pursuing a similar path to me through National Service, i.e., stay in Aldershot as a Drill

Instructor. I was already a sergeant by this time, and was in a position to recommend him for

promotion to Lance Corporal. He attained this without any opposition, and within a year, he became a

Corporal. He eventually made sergeant. At no time were any eyebrows raised, snide remarks made, or

obstacles put in this man’s way.

Military Gastronomy

"An army marches on its stomach" it has been said. Well, the Willems cook-house was a miserable

place. The breakfast fried eggs, laid out in orderly ranks on the hot-plate in their hundreds, were a

constant gastronomical challenge. We could have played tennis with them. Other meals were either

tasteless or excessively greasy. At most eating sessions an officer (usually a National Service 2nd

Lieutenant) would do the rounds asking if there were any complaints. "No Sir, thank you, Sir" was the

usual reply, even if the food was appalling, which invariably it was.

Again Willie Rushton’s experience is worth recounting:

"Everything all right, food all right?" - the Sergeant Major looking at us … I realised that I had found this leaf

- we were having some sort of stew, I don’t know what dead animal it was, but something obviously the Army

had bought en bloc. "Sergeant Major, there is a leaf in my stew." The Officer said, "That’s definitely a leaf."

So we paraded off, bringing the stew, to the kitchens, where there was a Sergeant Major, Cook, Head Chef

or whatever he was, standing there. "What’s this?" "It is a leaf. We can’t have leaves in the stew." The man

then pulled out this huge military manual of army cooking and turned to page 308 where it said: "Stew -

Other Ranks for the use of" and there was the "500 tons of beef, 4,000 tons of potato and onions - and - 1

bay leaf."

To give the Royal Army Catering Corps their due credit, if ever a special occasion came, such as a children’s

party or some other celebration, they could turn out a brilliant spread. Some of the most impressive

decorative iced cakes could have been seen in army kitchens.

After each meal we would troop out to a steaming metal bath of hot water in which we had to cleanse

our utensils (without the benefit of washing up liquid).

On occasions when we were out on major field exercises we would be introduced to the products of

army field kitchens. These included such culinary delights as tinned egg and bacon.

The grease that was not consumed with the food in the barracks cook-house eventually found its way

into the kitchen drainage system. At the rear of every cook-house was an enormous grease trap

designed to protect the town sewerage system from the ravages of military gastronomy, but which in

reality doubled up as a ready source of punishment for soldiers who fell foul of some disciplinary code

or other.

The worst punishment was to be told to don your "fatigues", open up the enormous lids to the stinking

black hole behind the cook-house, climb into it, then with a large scoop ladle out into buckets the

accumulated foetid layers of stinking greasy scum. This task always sorted out the men from the boys.

It was advisable always to follow up this activity with a long, hot bath!

Alcohol in Aldershot

There were at least ninety pubs in the town of Aldershot, and so we had ample opportunity during free

time to carry out experiments on how much alcohol could be poured into a young vertical human body

before it became a young horizontal human body. It was on one such expedition that I made first

contact with something called "rough" cider. The joke was that if you held your glass up to the light you

could still see pips and bits of apple core floating around, but the truth was that the term "rough"

related to (1) a high level of alcohol, and (2) how you would be feeling in a few hours time.

On that memorable summer evening, I and my thirsty comrades were having a cider drinking session in

one of Aldershot’s pubs. I was having a wonderful time, exchanging the best jokes in the world

(probably the worst jokes when sober), and had consumed about three pints of this fearsome brew in

very quick succession. I was laughing and joking with the best of them, but then I began to feel

somewhat detached from the world and decided to go outside into the street for some air.

It was then that I had the most remarkable experience: whilst I was standing bolt upright, the pavement

turned upwards through ninety degrees and hit me in the face!

It seemed an age before I deduced that both the pavement and I were horizontal. I staggered to my

feet and decided to try to walk back to the barracks. Although I accomplished this in due time, it was

through an eternity of nausea, and I am ashamed to say that Aldershot Corporation’s street cleansing

services would have been kept fairly busy the next day along my trail from the pub to the barracks.

When I got back to the barracks I had one last attempt at turning myself inside out in the nearest

ablutions block, then crawled up the stairs to my landing, where I vaguely remember being met by

some room mates, undressed by them, and put to bed. This was a little humiliating because I was at

that time the Room Corporal! Nobody mentioned it the next day and life went on as normal.

I have since come to the conclusion that allowing young people to make themselves thoroughly ill in a sea of

alcohol is probably not a bad thing, because the experience is so ghastly that it is unlikely to be repeated

(except by those with no intelligence). Certainly in my own case, whilst I plead guilty to becoming seriously

squiffy on special occasions, I have never ever repeated the rough cider experience.

Military Management Style

If you go on a typical management course you are taught how to motivate people, maintain their

respect and co-operation and achieve objectives by team work and good communication.

I learned during National Service that none of these aspirations was relevant to military operations. I

experienced an example of the peculiar military management style a few weeks after I had been

promoted to Sergeant. I was now a "Drill Pig", and so far as I was aware was successfully putting new

intakes through their drill training, passing drill competitions, and making a satisfactory spectacle for

proud parents who attended the Passing Out Parade at the end of basic training.

One Sunday night (actually it was 1 o’clock Monday morning) I returned to the Sergeants’ Mess having

used a week-end pass to go back home in Kingston trying to chat up girls. As usual, I was depressed.

Here I was, back amongst the gloomy buildings of Willems Barracks, with another week of square

bashing to look forward to. Just before I got to my room, I was intercepted by a Sergeants’ Mess

steward who had clearly been awaiting my return. I was tired, miserable, and ready for some sleep.

Then the bombshell: "You’d better come to the bar; you are in charge of it, as of now!"

So, while I had been away during the week-end, the Battalion Commander had decided, in the

interests of flexibility and general self-development that I should, without prior notice, be relieved of

my drill training duties and given responsibility for supervising the Sergeants’ Mess catering staff,

managing stock control in the Mess Bar, as well as actually serving behind the bar - which most nights

went on for indefinite periods, that is

until the last self-opinionated sergeant-

major couldn’t get any more beer down

his throat and felt like turning in for at

least two hours sleep before the next

Company Parade.

A more miserable time I have never had.

I had to manage sullen National

Servicemen who were deemed to be

good for nothing except to clean

kitchens and serve meals. Unlike my

green squaddies on the parade ground,

most of these guys didn’t give a damn

about my three stripes, and were as like

as not to beat me up if I tried too much

discipline. Their level of co-operation was in direct proportion to the amount of time they had left to

serve, which for most of them was very little.

At breakfast I was responsible for seeing that everyone got their eggs and bacon, and endless supplies

of toast, in good time for them to get out for their various duties. There was a big problem here, since

many of the people I was serving were senior in rank - staff sergeants, sergeant majors and so on,

some of whom were prone to rolling into the dining room rather late. I had received a direct order

from the Regimental Sergeant Major to stop serving breakfast at a particular time because of this

problem. When I tried to implement the Order, one of the staff sergeants who had come in late, sat at

a table which had been cleared because the deadline had passed, and demanded (indeed ordered) that

I should provide him with breakfast. No amount of reasoning would change his attitude, and when I

later complained to the RSM about it, he made it clear that it was my problem. On reflection, I

suppose it was: I should have refused the staff sergeant on the grounds that orders from the RSM took

precedence. But at the time I was not sufficiently mature.

It was a blessed relief after some weeks to be told that I was to resume normal training duties, these

being returned to me in the same perfunctory way as I had originally been relieved of them.

As a prisoner marks off the days on his cell wall, so we

marked off the days of National Service remaining to us.

As my count approached the two-year mark, I was

button-holed by the company sergeant major with an

invitation to sign on as a "Regular". He promised that

promotion to Staff Sergeant would be a certainty

immediately on signing up for another three years. As

usual, my vanity nearly got the better of me, but I was

relieved to hear myself say "No thank you, Sir."

(Remember "Boots"? ... he's behind me in the photo on

the right!)

A free Man of “Above-average Intelligence”

I left the Army with a surprisingly good reference from

the Commanding Officer written in the back of my

Certificate of National Service: Military Conduct: Very

Good. A non commissioned officer of above average

intelligence, ability and commitment; of excellent

character, he is absolutely loyal and trustworthy. He

has been an asset to his Battalion, as he must be to

any employer.

1st June 1958.

So I suppose I had a couple of things to be grateful for … the ability to touch-type, and a document

indicating that any employer would be mad not to put me on his payroll!

© Lionel Beck - North Yorkshire - UK

© Lionel Beck - North Yorkshire - UK

NATIONAL SERVICE

Two years compulsory

National Service in the

Royal Army Service Corps.

I progress from “Sprog” to

Drill Sergeant in the hell

hole that was 2 Training

Battalion, Willems

Barracks, Aldershot.

All the gory details, plus

photographs.

Keith Pritchard

I met Keith 2009. He

was a Tour Manager for

“Great Rail Journeys”

and he added great

value to our vacation in

France, cruising the river

Rhone on the “Princesse

de Provence”. He read

my page on losing my

daughter and sent me a

poem he wrote some

time ago during a low

period in his own life.

CHEER UP!

Jokes, funny stories

and general lunacy

from a variety of

sources, including

those circulated around

the Web

GEORGE W BUSH

(President of the USA

2000-2008) was

famously inept with the

construction of words and

sentences.

Here are a few examples

at which you can now

laugh with a clear

conscience since he is no

longer in such a powerful

position.

Laugh at the quotes and

be grateful that the USA

now has a President

whose first language is

English!

MAD YEAR 2002

For a couple of years I

kept a diary of some of the

sillier and/or otherwise

noteworthy occurrences

both in the UK and abroad.

This is how 2002 looked

through my jaundiced

eyes. The World in the

year after “9-11”

RHONE CRUISE 2009

A Great Rail Journeys

vacation: Eurostar to Lille,

northern France, TGV to

Lyon, southern France,

and a week’s cruising the

Rhône and Saône on the

Princesse de Provence.

Notes and photographs.

The Dreaded Day

To my great consternation (since I had already convinced myself that I was a

very sick person) the Medical Board that examined me for fitness to do

National Service thought otherwise and declared me to be in rude health. So in July 1956 I duly

reported to Waterloo Station and boarded a train with hundreds of other deeply unhappy young men

and travelled miserably to the less-than-exotic location of Aldershot, Hampshire, for basic training.

"Bring back National Service" has always been a popular cry in Britain, and I am always surprised that

some of the people repeating this mantra actually did National Service themselves! I suppose there

were some plus points: some people learned skills they might otherwise not have obtained. For myself,

I have never regretted being turned into a touch-typist (would you believe!). Also, I am sure that being

uprooted from the home environment eased the passage from boyhood to independent manhood. But

the downside was that all these young men who, whilst being deemed too young even to enjoy the

right to vote for their Government, were nevertheless deemed old enough to be sent into war

situations in remote parts of the world and be killed.

I suppose that if National Service were to be reintroduced now for eighteen year-olds then at least this time

they would be old enough to vote!

Putting Square Pegs in Round Holes

Basic training brought out the best and the worst in us. Those who lacked confidence became the

victims of those who didn’t. Those who were known to have had experience in school cadet forces

were given responsibility for marching their platoons from A to B when the NCOs couldn’t be bothered

to do it themselves. I was one such, and so found myself (without the benefit of any visible rank)

yelling at my fellow squaddies, and showing off my own drill skills to those poor unfortunates who had

not previously worn a uniform. As a means of gaining respect and popularity this was about as effective

as spitting in someone’s face.

During the first couple of weeks’ basic training (at Blenheim Barracks) each of us was interviewed by

an officer to establish in what direction we should be encouraged to go. Would we be put forward for a

Commission? (Even National Servicemen were picked (usually on a "class" basis) as potential 2nd

Lieutenants.) Would we become lorry drivers? Would we become cooks? Would we become

infantrymen, wireless operators, mechanics? If we were not potential officers, could we be potential

Non-commissioned Officers (NCOs)?

The officer who interviewed me appeared to make an early decision (from my accent?) that I was not

officer material. Having decided that I ought at least to try and enjoy myself, I said I would like to

drive a lorry: after all, the RASC was responsible for, amongst other things, transport. In line with what

passed for military logic this resulted in my being ear-marked as an Army Clerk! I was sent to the RASC

2 Training Battalion, Willems Barracks, to be suitably trained. The Royal Army Service Corps (variously

referred to as "Run Away Someone’s Coming" the "Royal Army Shit Corp" and the "Royal Army Skirt

Chasers") not only provided the army with its transport but also its clerical services, i.e., short-hand

writers, typists, secretaries, filing clerks, and so on.

Military Type

The Army had, in its wisdom, decided that I should join a "Clerical

Battalion".

The Pen is mightier than the Sword?

So I - with my fellow sufferers earmarked as clerks - headed for 2

Trg Bn at Willems Barracks where the next four weeks were spent

completing basic training in drill and weaponry, combined with

training in basic typing skills and the mysteries of memos, files and

dockets.

For the typing we were assembled in a class room equipped with

rows of ancient typewriters. The sergeant in charge taught us the

position of the "home keys".

You hover the left hand over A S D and F, and the right hand over : L K and J. From here all other keys can

be reached merely by moving one’s fingers forwards or backwards, and/or slightly to right or left. The next

thing is to remember where all these keys are without looking at the keyboard; this skill came fairly quickly

to most of us, (1) because we did nothing else for two hours at a time, and (2) because when a man wearing

three stripes tells you to do something you don’t argue.

Within a few days the Sergeant was playing marching music on a record player at the front of the class,

and we were copy-typing pieces of text in strict time to the beat, without taking our eyes off the

paper.

Fifty years later I am sitting in front of a computer keyboard typing this account at sixty words per minute

without looking at the keys, grateful to the Army for this particular ability.

From Typist to “Drill Pig”

For all my quickly-developing skills as an army typist, I nurtured no desire

to serve out the rest of my National Service sitting in Army offices, be

they brick or canvas. Whilst many of my comrades were keen to be sent

abroad, my unadventurous disposition was more inclined to keeping out of

war zones, and preferably staying within commuting distance of home. It

was at this time that Prime Minister Anthony Eden’s Suez Crisis

developed. I was very keen to avoid any opportunity to go and kick the

Egyptian President’s backside in that particular bungled operation.

I soon learned there was a continual need for National Service NCOs to

help train up further intakes of miserable young men, appearing as they

did every four weeks on the National Service conveyor belt. Again, calling

on my experience as a Sergeant in the school cadet force, I was able to

gain rapid promotion to Lance Corporal on completion of my basic training, and it wasn’t too long

before I was a full Corporal and feeling pretty damned pleased with myself.

This added a few shillings to my miserable weekly pay, so there was added cash to spend on packets of

five "Park Drive" or "Woodbines", or - more nutritiously - double portions of baked beans in the NAAFI.

Armed with my new stripes and a long stick with a silver knob on the end

I was assigned to help a National Service Sergeant in marching squads of

men up and down the drill square, right-turning, left-turning and about

turning, shouldering arms, ordering arms, standing to attention, standing

at ease and standing easy. Other duties included ensuring that a barrack

room full of men got up in the morning in time to wash, shave, dress,

clean the room, lay out kit in regulation order, have breakfast and be on

parade by 07.30 hours.

How I admired our National Service Sergeant Copage! Immaculately

turned out with his toe caps reflecting the early morning sun, he had a

voice that could be heard two miles away, and a fine selection of

personal insults to heap on the first poor soul to swing his right arm

forward at the same time as his right leg went forward. (There was

always one!) I resolved to model myself on Sgt Copage. In a rare burst of

ambition, I thought that if he could make sergeant before reaching the

age of twenty, then so could I.

This ambition to reach sergeant before completion of National Service was the first of only a very few

instances in my life when I set a specific target for my future.

You may think that you can control your life, map out your future, set your long-term targets. I advise

caution. If you must have an ambition, stick to generalities and don’t be too specific. Life has a nasty habit

of moving (or removing) your targets before you’ve had time to hit them. The more you plan in detail, the

more you lay yourself open to disappointment.

Look at where you would like to go and set your compass, but don’t draw a detailed route map. You don’t

have to be religious to appreciate one of the greatest pieces of advice from Jesus: "Give no thought for the

morrow, for sufficient unto the day are the evils thereof." In today’s English, if you spend all your time

worrying about the future, there’s no happiness; there are enough of today’s problems for you to be

worrying about.

It has been said that there is no destination in life - the journey is everything. I don’t know who said it. I

think I just did.

The late, great Willie Rushton, interviewed shortly before his untimely death in 1997 about his own

National Service experiences said,

"…the NCOs we always viewed as traitors because they were all NATIONAL SERVICE men and

almost invariably DEEPLY UNPLEASANT."

With the benefit of hindsight plus increasing maturity I have to acknowledge that Rushton's comment

could have applied to me. It is not a period of which I am particularly proud. I sometimes recall,

though, to make myself feel better, that not one my men ever tried to throw a brick at the back of my

head on a dark night, and some intakes even clubbed together and bought me a gift at the end of their

training. This was very gratifying, though not, I think, well deserved.

But I worked with National Service colleagues who were more fanatical than me. One Corporal (who

used to keep his brilliantly shiny "best" boots in a cardboard box wrapped in tissue paper, and was thus

known to all as "Boots") was such a perfectionist that on one occasion when we were working together

on the parade ground he insisted on putting his squad through their miserable paces right through the

sacred "NAAFI Break" because they were not measuring up to his exacting standards. This tall, thin

gangly youth of nineteen, with his razor-sharp creases and his glittering boots, yelled and bawled

obscenities at his victims, and their consequent efficiency was in inverse proportion to the volume of

the shouting. They were not going to get any better because they were tired, and all they could think

about was the fact that they were being denied the opportunity of getting their mug of tea and

lighting up a Woodbine. Whatever else I might have been I did believe in fair play, and things were

getting so objectionable that I gave a direct order to this maniac to dismiss his men. It was several

weeks before he could bring himself to speak to me again, and I didn’t regard this as a great loss.

During those days if you were in a Training Battalion, the majority of the personnel were conscripted

National Servicemen, and these included the NCOs and junior commissioned officers, but naturally

there was a core of regular soldiers at the heart of the system: the lieutenants, captains, majors, and

colonels on the commissioned side, and on the non-commissioned side, the sergeants, staff sergeants,

company sergeant majors and regimental sergeant majors. National Service NCOs rarely had time in

two years to make it beyond sergeant, nor National Service officers beyond 2nd lieutenant.

Some of us had a nasty habit of referring to the professionals as "Thick Regulars", for we could not

imagine that anyone with an ounce of intelligence would actually have chosen this way of life as a

career! The antipathy operated in both directions. In the Sergeants’ Mess, the National Service

sergeants were looked down upon by the regulars as presumptuous upstarts. No doubt similar feelings

existed in the Officers’ Mess, but possibly restrained under a more gentlemanly veneer; perhaps not.

The truth of the matter was, if we were honest, that although it was easy to

identify some regular soldiers (and National Servicemen!) who were a couple of

rounds short of a full magazine, many were intelligent and honourable men. I

was glad to regard some of them of as my friends. Our B Coy Sergeant Major-

and here he is on the right - was a really first-class character with a sense of

humour and a genuine regard for the men under his command. I had forgotten

his name but I am grateful to George Goult (ex-NS sergeant who was discharged

a month before me) who wrote to me in 2008 and put me out of my misery. This

was CSM SYMES - a gentleman.

On the other hand, the Company Commander was one of the vilest characters

I’ve had the misfortune to meet: sarcastic, supercilious, vindictive and arrogant,

with a distinctly cruel streak, and the owner of a large Mercedes-Benz which

sparkled and gleamed down to the number plate screw heads, thanks to the

detailed attention required of any soldier who was given the unfortunate task of

cleaning it to his satisfaction. I also forgot this man's name, but I am grateful (I

think!) to Peter Claridge (who entered Willems for trade training in November 1957) for e-mailing me

with the missing name .. Major McCarten-Mooney.

Racism in the Army, Navy and Air Force has been a topical subject during recent years. There have

been some widely reported cases of anti-black feeling in certain regiments, (especially the Guards)

involving bullying and harassment, leading to the victims’ resignation from the Service.

All the more heartening to recount, therefore, that during my two years in Aldershot back in the

deeply prejudiced mid-1950s, I did not encounter active racism in my particular part of the RASC. In

fact I recall very clearly one recruit of Afro-Caribbean origin who I came to know quite well; he was

keen on pursuing a similar path to me through National Service, i.e., stay in Aldershot as a Drill

Instructor. I was already a sergeant by this time, and was in a position to recommend him for

promotion to Lance Corporal. He attained this without any opposition, and within a year, he became a

Corporal. He eventually made sergeant. At no time were any eyebrows raised, snide remarks made, or

obstacles put in this man’s way.

Military Gastronomy

"An army marches on its stomach" it has been said. Well, the Willems cook-house was a miserable

place. The breakfast fried eggs, laid out in orderly ranks on the hot-plate in their hundreds, were a

constant gastronomical challenge. We could have played tennis with them. Other meals were either

tasteless or excessively greasy. At most eating sessions an officer (usually a National Service 2nd

Lieutenant) would do the rounds asking if there were any complaints. "No Sir, thank you, Sir" was the

usual reply, even if the food was appalling, which invariably it was.

Again Willie Rushton’s experience is worth recounting:

"Everything all right, food all right?" - the Sergeant Major looking at us … I realised that I had found this leaf

- we were having some sort of stew, I don’t know what dead animal it was, but something obviously the Army

had bought en bloc. "Sergeant Major, there is a leaf in my stew." The Officer said, "That’s definitely a leaf."

So we paraded off, bringing the stew, to the kitchens, where there was a Sergeant Major, Cook, Head Chef

or whatever he was, standing there. "What’s this?" "It is a leaf. We can’t have leaves in the stew." The man

then pulled out this huge military manual of army cooking and turned to page 308 where it said: "Stew -

Other Ranks for the use of" and there was the "500 tons of beef, 4,000 tons of potato and onions - and - 1

bay leaf."

To give the Royal Army Catering Corps their due credit, if ever a special occasion came, such as a children’s

party or some other celebration, they could turn out a brilliant spread. Some of the most impressive

decorative iced cakes could have been seen in army kitchens.

After each meal we would troop out to a steaming metal bath of hot water in which we had to cleanse

our utensils (without the benefit of washing up liquid).

On occasions when we were out on major field exercises we would be introduced to the products of

army field kitchens. These included such culinary delights as tinned egg and bacon.

The grease that was not consumed with the food in the barracks cook-house eventually found its way

into the kitchen drainage system. At the rear of every cook-house was an enormous grease trap

designed to protect the town sewerage system from the ravages of military gastronomy, but which in

reality doubled up as a ready source of punishment for soldiers who fell foul of some disciplinary code

or other.

The worst punishment was to be told to don your "fatigues", open up the enormous lids to the stinking

black hole behind the cook-house, climb into it, then with a large scoop ladle out into buckets the

accumulated foetid layers of stinking greasy scum. This task always sorted out the men from the boys.

It was advisable always to follow up this activity with a long, hot bath!

Alcohol in Aldershot

There were at least ninety pubs in the town of Aldershot, and so we had ample opportunity during free

time to carry out experiments on how much alcohol could be poured into a young vertical human body

before it became a young horizontal human body. It was on one such expedition that I made first

contact with something called "rough" cider. The joke was that if you held your glass up to the light you

could still see pips and bits of apple core floating around, but the truth was that the term "rough"

related to (1) a high level of alcohol, and (2) how you would be feeling in a few hours time.

On that memorable summer evening, I and my thirsty comrades were having a cider drinking session in

one of Aldershot’s pubs. I was having a wonderful time, exchanging the best jokes in the world

(probably the worst jokes when sober), and had consumed about three pints of this fearsome brew in

very quick succession. I was laughing and joking with the best of them, but then I began to feel

somewhat detached from the world and decided to go outside into the street for some air.

It was then that I had the most remarkable experience: whilst I was standing bolt upright, the pavement

turned upwards through ninety degrees and hit me in the face!

It seemed an age before I deduced that both the pavement and I were horizontal. I staggered to my

feet and decided to try to walk back to the barracks. Although I accomplished this in due time, it was

through an eternity of nausea, and I am ashamed to say that Aldershot Corporation’s street cleansing

services would have been kept fairly busy the next day along my trail from the pub to the barracks.

When I got back to the barracks I had one last attempt at turning myself inside out in the nearest

ablutions block, then crawled up the stairs to my landing, where I vaguely remember being met by

some room mates, undressed by them, and put to bed. This was a little humiliating because I was at

that time the Room Corporal! Nobody mentioned it the next day and life went on as normal.

I have since come to the conclusion that allowing young people to make themselves thoroughly ill in a sea of

alcohol is probably not a bad thing, because the experience is so ghastly that it is unlikely to be repeated

(except by those with no intelligence). Certainly in my own case, whilst I plead guilty to becoming seriously

squiffy on special occasions, I have never ever repeated the rough cider experience.

Military Management Style

If you go on a typical management course you are taught how to motivate people, maintain their

respect and co-operation and achieve objectives by team work and good communication.

I learned during National Service that none of these aspirations was relevant to military operations. I

experienced an example of the peculiar military management style a few weeks after I had been

promoted to Sergeant. I was now a "Drill Pig", and so far as I was aware was successfully putting new

intakes through their drill training, passing drill competitions, and making a satisfactory spectacle for

proud parents who attended the Passing Out Parade at the end of basic training.

One Sunday night (actually it was 1 o’clock Monday morning) I returned to the Sergeants’ Mess having

used a week-end pass to go back home in Kingston trying to chat up girls. As usual, I was depressed.

Here I was, back amongst the gloomy buildings of Willems Barracks, with another week of square

bashing to look forward to. Just before I got to my room, I was intercepted by a Sergeants’ Mess

steward who had clearly been awaiting my return. I was tired, miserable, and ready for some sleep.

Then the bombshell: "You’d better come to the bar; you are in charge of it, as of now!"

So, while I had been away during the week-end, the Battalion Commander had decided, in the

interests of flexibility and general self-development that I should, without prior notice, be relieved of

my drill training duties and given responsibility for supervising the Sergeants’ Mess catering staff,

managing stock control in the Mess Bar, as well as actually serving behind the bar - which most nights

went on for indefinite periods, that is

until the last self-opinionated sergeant-

major couldn’t get any more beer down

his throat and felt like turning in for at

least two hours sleep before the next

Company Parade.

A more miserable time I have never had.

I had to manage sullen National

Servicemen who were deemed to be

good for nothing except to clean

kitchens and serve meals. Unlike my

green squaddies on the parade ground,

most of these guys didn’t give a damn

about my three stripes, and were as like

as not to beat me up if I tried too much

discipline. Their level of co-operation was in direct proportion to the amount of time they had left to

serve, which for most of them was very little.

At breakfast I was responsible for seeing that everyone got their eggs and bacon, and endless supplies

of toast, in good time for them to get out for their various duties. There was a big problem here, since

many of the people I was serving were senior in rank - staff sergeants, sergeant majors and so on,

some of whom were prone to rolling into the dining room rather late. I had received a direct order

from the Regimental Sergeant Major to stop serving breakfast at a particular time because of this

problem. When I tried to implement the Order, one of the staff sergeants who had come in late, sat at

a table which had been cleared because the deadline had passed, and demanded (indeed ordered) that

I should provide him with breakfast. No amount of reasoning would change his attitude, and when I

later complained to the RSM about it, he made it clear that it was my problem. On reflection, I

suppose it was: I should have refused the staff sergeant on the grounds that orders from the RSM took

precedence. But at the time I was not sufficiently mature.

It was a blessed relief after some weeks to be told that I was to resume normal training duties, these

being returned to me in the same perfunctory way as I had originally been relieved of them.

As a prisoner marks off the days on his cell wall, so we

marked off the days of National Service remaining to us.

As my count approached the two-year mark, I was

button-holed by the company sergeant major with an

invitation to sign on as a "Regular". He promised that

promotion to Staff Sergeant would be a certainty

immediately on signing up for another three years. As

usual, my vanity nearly got the better of me, but I was

relieved to hear myself say "No thank you, Sir."

(Remember "Boots"? ... he's behind me in the photo on

the right!)

A free Man of “Above-average Intelligence”

I left the Army with a surprisingly good reference from

the Commanding Officer written in the back of my

Certificate of National Service: Military Conduct: Very

Good. A non commissioned officer of above average

intelligence, ability and commitment; of excellent

character, he is absolutely loyal and trustworthy. He

has been an asset to his Battalion, as he must be to

any employer.

1st June 1958.

So I suppose I had a couple of things to be grateful for … the ability to touch-type, and a document

indicating that any employer would be mad not to put me on his payroll!

The Dreaded Day

To my great consternation (since I had already convinced myself that I was a

very sick person) the Medical Board that examined me for fitness to do

National Service thought otherwise and declared me to be in rude health. So in July 1956 I duly

reported to Waterloo Station and boarded a train with hundreds of other deeply unhappy young men

and travelled miserably to the less-than-exotic location of Aldershot, Hampshire, for basic training.

"Bring back National Service" has always been a popular cry in Britain, and I am always surprised that

some of the people repeating this mantra actually did National Service themselves! I suppose there

were some plus points: some people learned skills they might otherwise not have obtained. For myself,

I have never regretted being turned into a touch-typist (would you believe!). Also, I am sure that being

uprooted from the home environment eased the passage from boyhood to independent manhood. But

the downside was that all these young men who, whilst being deemed too young even to enjoy the

right to vote for their Government, were nevertheless deemed old enough to be sent into war

situations in remote parts of the world and be killed.

I suppose that if National Service were to be reintroduced now for eighteen year-olds then at least this time

they would be old enough to vote!

Putting Square Pegs in Round Holes

Basic training brought out the best and the worst in us. Those who lacked confidence became the

victims of those who didn’t. Those who were known to have had experience in school cadet forces

were given responsibility for marching their platoons from A to B when the NCOs couldn’t be bothered

to do it themselves. I was one such, and so found myself (without the benefit of any visible rank)

yelling at my fellow squaddies, and showing off my own drill skills to those poor unfortunates who had

not previously worn a uniform. As a means of gaining respect and popularity this was about as effective

as spitting in someone’s face.